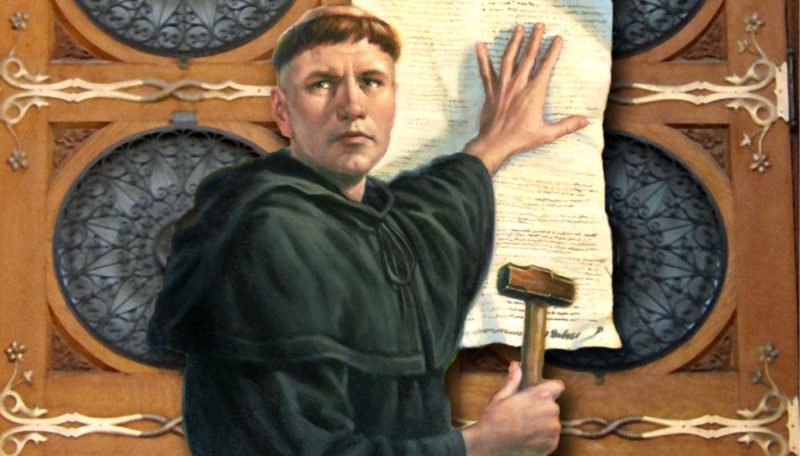

Some thoughts on the Protestant Revolution

بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم

I’ve become more sympathetic to the Protestant revolution as a result of learning more about the systematic abuses of the Church circa 1200-1500.

Previously, I had held, a la Guenon that the Protestant revolution was merely a deviation from tradition and one of the important milestones in the birth of the modern mindset which so destroyed revealed values.

I still hold this position to be broadly correct. However, when I read that it had become socially acceptable for priests to take concubines because the Church would not allow them to marry, or how rich and powerful bishops regularly hosted orgies of such magnitude that would make politicians today blush, or when I read about the sale of indulgences, I cannot help but find within myself the glimmer of a Lutherian spirit of outrage growing.

It has also given me a greater appreciation of the Prophet saying “Every [religious] innovation is a deviation, and every deviation is in the hellfire.” One of the catalysts to the unbelievable and quite scandalous lechery which spread throughout the Church and is still present till today is exactly the Pope’s innovation of preventing priests from marrying, opening up the door to all sorts of sexual immorality and deviancy.

I also have gained a greater appreciation for the ways in which this movement was different than the Wahhabi movement despite holding similar doctrines (e.g. sola scripture = return to the Quran and Sunnah, everyone reading the original sources for their own, tradition holding no authority, calling on saints/visiting shrines being idolatry, etc.). Protestantism was born out of a genuine desire to reform the Church due to clear moral corruption and the theology was developed in reaction to this. Wahhabism, on the other hand, did not criticize the general masses of Muslims/ulema/state structures primarily on the basis of clear moral corruption. On the contrary, Wahhabism emerged at a time when the spiritual strength of the ummah was still high, and the people and scholars still possessed a large degree of piety. Rather, it seems that Wahhabism was a theology first movement combined with political motives which then problematized the everyday piety of the Muslim masses.

I have also come to more greatly appreciate that when ulema have shortcomings, the ramifications of that upon the general population are not to be underestimated. The clergy had long lost respect among the everyday population probably for at least a century before the Protestant revolution had happened, which is why when it took off it spread like wildfire.

I am still learning about this interesting time period, and these are simply some initial reflections.